Discover the museums of considerable importance and all the artistic treasures of Gallarate near Malpensa Airport.

The two most characteristic churches of Gallarate which date back to different eras, are located in the same square. This is due to the need of the faithful to be able to worship when high tide prevented them crossing the bridge over the two streams which once flowed. Today, in the same spot, you can see the fountain that faces the Basilica. Over time, the course of the thousand-year-old streams has been diverted due to frequent floods, and today they flow outside the historic centre. In their place, streets and squares with cobbled pavement delimit the current pedestrian area.

Basilica di Santa Maria Assunta in piazza Libertà, 1870

The imposing Basilica stands where the ancient church once was. This, in turn, was built on the area where the medieval castle, demolished in 1362, once stood. Expansion of the existing religious building was necessary due to the growing population. This was a result of the considerable industrial development and urban growth of the city in the mid-1800s. Also, the need for a monument to represent the grandeur and profound devotion of the population.

Construction and decoration

The construction and decoration was made possible thanks to a bequest in 1842. This is on behalf of Giuseppe Cagnoni for the construction of a new religious building for Gallarate. Also, principally thanks to donations from the wealthiest Gallarate families such as the Cantoni, Borghi and Ponti. Also because they called the best architects, craftsmen and decorators of the time to execute the frescoes, decorations and stained glass windows. Construction began in 1856 on a project by the Milanese architect Giacomo Moraglia. However, it remained incomplete due to the sudden death of Moraglia in 1860. Only in 1868 were the works resumed, then completed in 1870 following a project by the architect Camillo Boito.

The building was finally consecrated in 1870 by the Archbishop of Milan, Monsignor Luigi Nazari di Calabiana. Following the new city regulatory plan of the 1930s, which provided for a thinning out and isolation of the monumental buildings, the buildings around the Basilica were demolished and the new baptistery built to a design by the architect Ambrogio Annoni featuring the panel Baptism of Jesus in the waters of the Jordan by Nicolò Pisano.

The mosaic floor

Furthermore, the new mosaic floor and marble slabs were created between 1925 and 1933, based on a project by the architect Romeo Moretti. In 1946, Pope Pius XII gave the church the title of Basilica Minore Romana. That was an honorary denomination granted to particularly important Catholic religious buildings, attributing the rank of basilica to them. On the occasion of the Jubilee of 2000, it was counted among the Jubilee churches.

The basilica is rich in paintings, statues, frescoes, stuccos, stained glass windows, gilded capitals and elaborate architectural structures that need attention. Restorations were carried out for the centenary, and the latest works, which began in 2015 and lasted until 2018, re-established the scenographic impact of the columns, restoring the original pinkish tones of the material.

Modern innovations

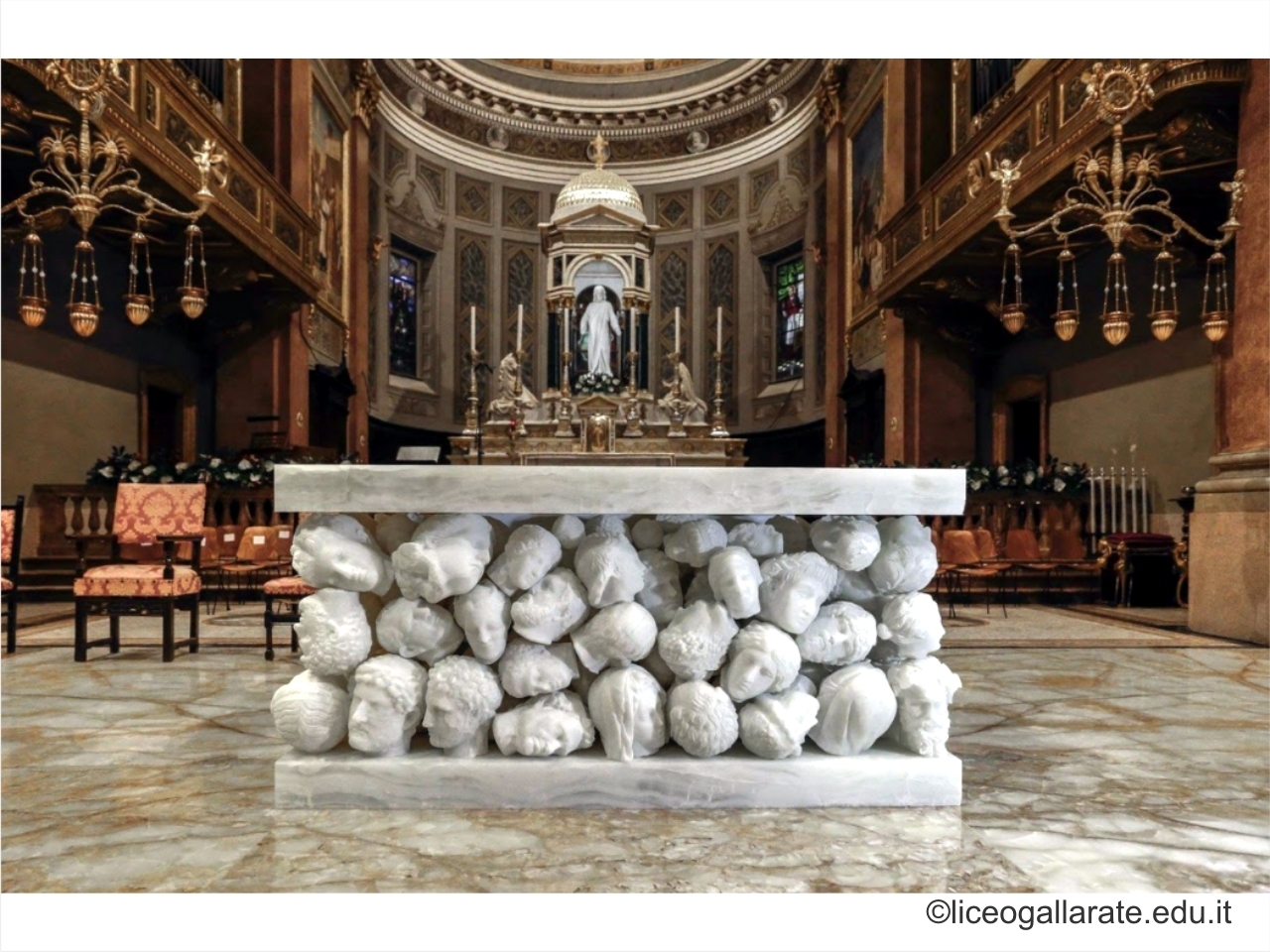

Furthermore, innovations were made possible thanks to the intervention of Claudio Parmiggiani. As one of the protagonists of the international artistic avant-garde movement, he created the new altar consisting of two marble slabs which hold and protect a multitude of ancient heads in white onyx. These heads depict copies of famous pieces from art history, sacred relics and emblems depicting humanity and all the famous saints, ancient men, philosophers, artists and symbolic figures, from the Belvedere Apollo to Michelangelo’s Virgin of Pietà, and up to Bernini.

The intent of the work is to represent the entire history of man through the most noble testimonies as a symbol of humanity waiting to be redeemed. In the photos are images of the current Basilica after its latest restoration: facade, nave, decorative details, dome, altar by Parmiggiani. Photo www.liceogallarate.edu.it

Ancient fortress complex

Of the ancient fortress complex, one of the ancient defensive towers was preserved, and was raised to a height of 45 meters and adapted to the new function of bell tower with a pavilion roof. Each side of the tower is characterised by vertical partitions divided horizontally by three series of round arches.

The bells are placed in the upper cell, while in the lower cell, you can see two rose windows with radiant suns and the monogram of Jesus J.H.S. and the date 1494 on the central rib. In the central band, under the clock face, you’ll see small basins in glazed ceramic by Albino Reggiori, a very common custom in the Middle Ages to increase the chromatic effect of the brick red. In the lower part, there is a walled-up plaque from the Roman era whose plaster cast is kept in the Museo degli Studi Patri. The tower was restored in the 90s by the architect George Luini.

Romanesque tower and neo-classical facade

The Romanesque tower contrasts with the neo-classical appearance of the new church whose facade rises to over three meters above a large churchyard. this was built in 1953 by the architect Moretti and the engineer Lombezzi in honor of Monsignor Simbardi. Above the three entrance doors, three bas-reliefs represent: “San Carlo Borromeo on a pastoral visit to Gallarate in 1570”, “The Annunciation”, and “Captain Annibale Cacccarana asking forgiveness from Cardinal Federigo Borromeo who had excommunicated him”.

A pair of Ionic columns support the entablature which has a curved front. In the upper part, four Doric semi-columns support the pediment with a triangular tympanum on which the statue of the Virgin of the Assumption rises in the center with two adoring angels on the sides, and divide the main facade into three parts. On the sides of each part there are niches housing statues of San Cristoforo, patron saint of the city on the right, and Sant’Eurosia co-patron saint on the left in the center, while a large window opens in the center. Two pilasters placed on the rearmost sides close the facade.

Interior

The interior is impressive for its size. For instance, the single nave is 89 meters long, 17.30 meters wide and 17.75 meters high and is marked by a succession of 18 Corinthian columns along the walls which have 12 niches featuring the statues of the Apostles, and 18 bas-relief panels illustrating various episodes from the life of the Virgin Mary. On the frieze, 71 medallions in high relief depict faces of saints and martyrs of the Church.

The decorations are the work of Celso Stocchetti and Carlo Maciachini, the architect and decorator well-known in Milan for their Monumental Cemetery project. Other decorators include Giovanni Bertini, Antonio Soldini and Giacomo Sozzi. On the sides of the nave, there are six chapels, three on each side. Starting from the entrance on the left, these chapels are dedicated to:

San Carlo Borromeo

A large painting from 1876 by De Belly depicts the Saint with San Luigi Gonzaga, and on the sides frescoes are paintings of the Doctors of the Church San Gerolamo and Sant’Agostino.

Santa Maria Assunta

Imposing marble carving made up of the Virgin, the child and two angels, by the Gallaratese sculptor Giuseppe Rusnati, who was actively involved in the work for the Cathedral of Milan, executed in 1698 and belonged to the previous church.

St. Joseph

Statue of the saint by Odoardo Tabacchi and frescoes of St. Mark and St. John.

The Immaculate

Taken from the name of the 15th-century wooden statue from the former Franciscan convent, part of which was demolished, and part of which has partly become the seat of the Museo degli Studi Patri, which was moved to the previous church following the wishes of the population.

St. John the Baptist

Statue by the sculptor Giovanni Duprè and frescoes by the Doctors of the Church San Gregorio Magno and Sant’Ambrogio.

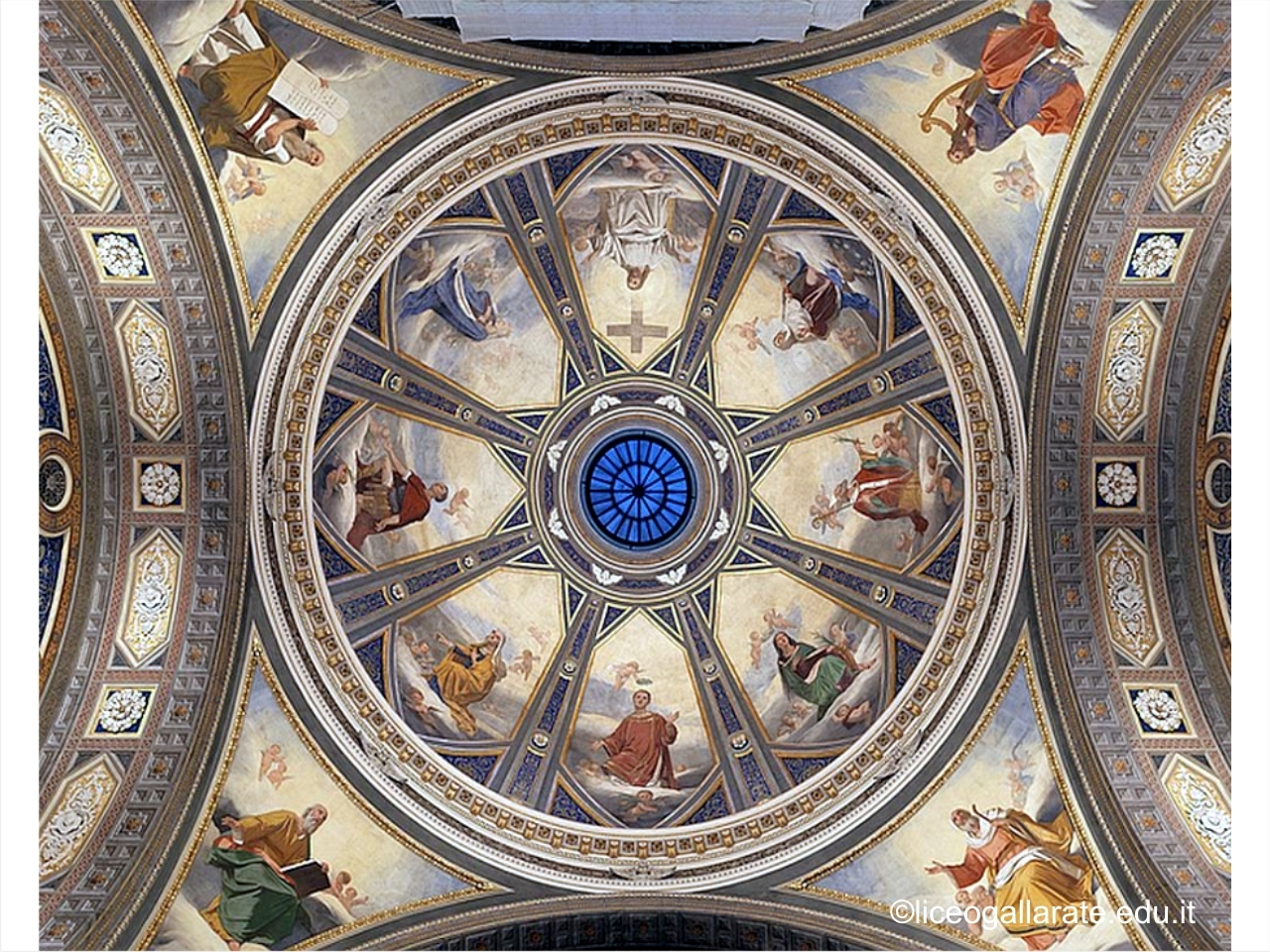

At the center stands the majestic dome, one of the largest in Lombardy. 18 meters in diameter and 29 meters high, with frescoes painted between 1888 and 1891 by Luigi Cavenaghi, an artist born in Caravaggio who, after studying in Brera, made a name for himself with numerous projects in Milan, including the decoration of the apses of the church of San Babila. The vault depicts the allegories of Justice and Charity and the coronation of the Virgin in the area near the Presbytery, and is particularly important due to its considerable size and the solemnity of its depictions.

The four spandrels depict the Patriarchs Adam, Isaiah, Moses and David, while in the eight segments of the dome we recognize Saint Stephen, Saint Lucia, Saint Sebastian, Saint Eurosia, the Risen Jesus, Saint Apollonia, Saint Calimero and Saint Catherine of Alexandria . In the video, the architect Paolo Martinelli takes us to visit the nooks and crannies of the Basilica starting from the large dome with its spectacular internal decorations.

The bell tower

Going up to the bell tower you can admire the wonderful view of the Crenna hills and the Sacro Monte di Varese, and when you come back down, you can see the two pulpits placed on red marble bases surmounted by lions, one intended for reading the Gospel and the other for reading the Epistles, pointing out that they are recognized by the figures who hold it: the evangelists for the first, and the doctors of the Church in the second.

The light filters through the sixteen multicoloured stained glass windows which illustrate episodes from the life of Jesus, the Virgin and the Saints, and were executed in different eras by various artists. On the counter-façade above the main portal, there is a beautiful stained glass window depicting the “Immaculate Virgin assumed into heaven” made by the Lezner company of Munich, considered the best glassware makers of the time.

Presbytery

The Presbytery, bordered off from the area of the faithful by austere stone balustrades, is surmounted by a pair of balconies on which the imposing organ, built in 1987, stands. Under the right balcony is a canvas dating back to the 17th century depicting the patron Saint Cristoforo, while below the one on the left is a depiction of the previous demolished church. The high altar is the work of Odoardo Tabacchi and consists of a neoclassical temple with eight Corinthian columns in green marble that support a mini dome, with the marble statue of Christ the Redeemer inside.

On the walls of the apse are three windows depicting, from the left, San Cristoforo, the Apostle Peter and San Carlo Borromeo. On the right side of the Presbytery is the new sacristy, created with the aim of protecting and showcasing some artistic elements of the previous Basilica, including the ‘sky’ of the 18th-century baldachin, among the best to be found in all of the churches of the Ambrosian towns, and made of quilted red brocade embroidered by Ferrano of Milan with pure gold and silver threads. It was used for the first time in 1745 and in 1805 for the coronation of Napoleon, King of Italy, in the Cathedral of Milan, and, due to its rarity, has attracted people from other cities everywhere who come to admire the richness of its design.

Chiesa di San Pietro in piazza Libertà, XI-XII century

The second religious building in the square is the oldest and best known in Gallarate from an artistic point of view, and is the little church dedicated to San Pietro, declared a National Monument in 1864, whose construction is believed to date back to the 11th-12th century, in the middle of the Late Middle Ages, a period in which Gallarate was divided into cantons and characterized by walls, towers and its castle.

The church is believed to be the work of the Comacini Masters (a group of builders, masons, plasterers and artists working since the 7th century in the areas of Como, Can Ticino and Lombardy in general, and among the first masters of the Lombard Romanesque style) and is considered to be one of the most beautiful examples of its time and among the best preserved. San Pietro church has a stone wall facade very similar to that of the church of Santi Pietro e Paolo di Brebbia, also in the province of Varese, suggesting it was similarly made with blocks of serizzo, granite and stone from Angera.

Structure trasformation

It still has its original architectural structure even although it has undergone multiple interventions and transformations over the centuries, as well as changes in function. The two-order gabled façade is characterized, at mid-height, by a blind loggia of intertwined round arches resting on columns or corbels carved with capitals with heads and zoomorphic motifs, and by two small rhomboidal Gothic windows with multicoloured glass representing the symbols of the city.

The entrance, off-centre to the right, is dominated by a half-moon mosaic made in 1920 by Angelo Gianusi and the Mosaic School of Spilimbergo in Venice, featuring St. Peter and St. Paul. At the center of the upper part there is a large circular window with a multicoloured stained glass window representing Christ in the act of handing over the keys to St. Peter. Finally, on the right buttress, a figure with female features carved in stone is visible.

Side view

The side elevation is made up of three bays and is a continuation of the loggia of intertwined sixth arches, along which you can catch glimpses of three large circular windows and decorative motifs that seem to recall ancient idols. Along the second bay, there is a secondary entrance to the church. While, the side ends with a metal structure at the level of the eaves which was used to house the ancient bells which were once part of the demolished bell tower. The apse, also with an arched loggia, was entirely rebuilt in the shape of a semicircle and has three loopholes.

Interiors

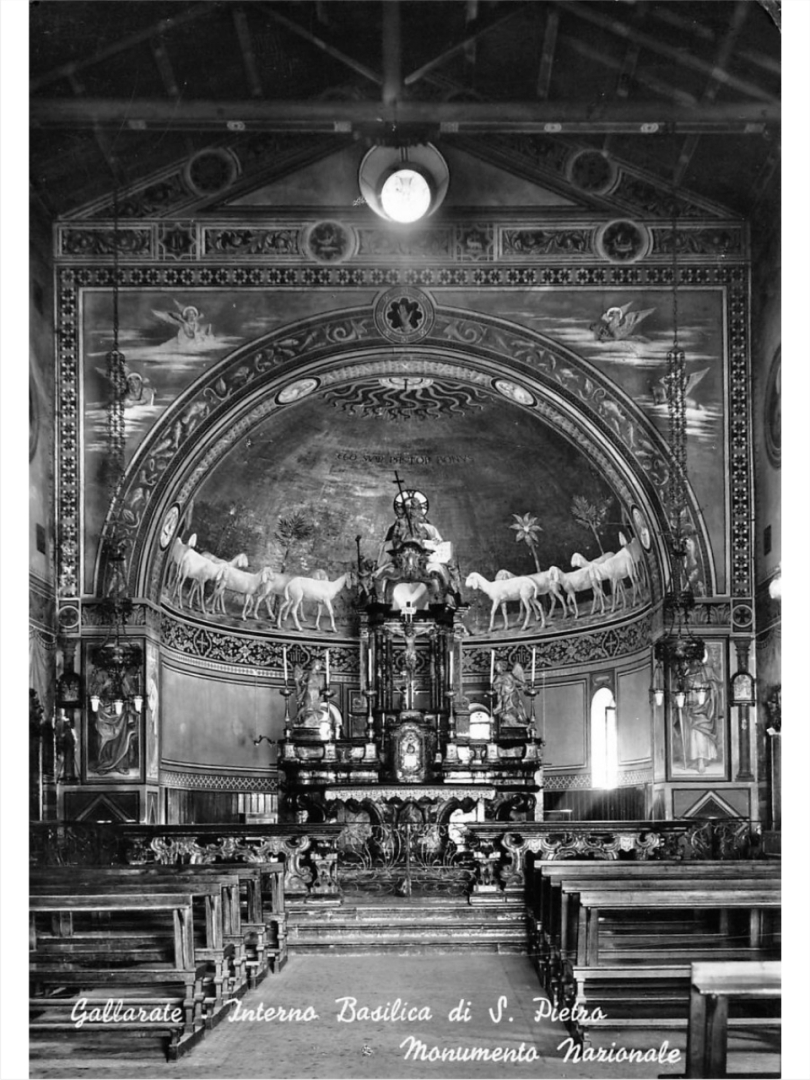

The interior has a single nave with a rectangular plan with an exposed trussed roof and a terracotta floor. A large part of the cycle of frescoes created by Ernesto Rusca between 1907 and 1910 has been lost due to humidity, so some swathes of material were added to the base as a nod to the ancient tapestries that adorned the church in the past. On the walls, inside round frames, the 12 apostles are depicted, while in the middle of the left wall there is a copy of the Virgin of Czestochowa, also known as the Black Madonna, very dear to the people of Gallarate.

This piece was donated to pilgrims led by Monsignor Lodovico Gianazza visiting Krakow in 1974, by the then Archbishop Mons. Carol Wojtyla, later proclaimed beloved Pope John II in 1978. At the base of the vaulted arch of the presbytery there are depictions of Saints Peter and Ilario to the left of the altar, and Saints Jerome and Paul to the right. The upper part of the wall is decorated with symbols of the Evangelists and depicts the hand of God the Creator symbolising life. Three steps up, the presbytery,is enclosed by two polychrome marble Baroque balustrades with a golden “rocaille” motif in the centre, while the altar, also in the polychrome marble Baroque style, is of the small temple type, surmounted by angels with symbols of passion, and other larger adorers on both sides.

Top view

The upper part of the interior of the apse is frescoed with fake mosaics and depicts Jesus enthroned in the guise of the Good Shepherd bringing blessings and holding the Gospel, and surrounded by his flock to the right and to the left. Seem to refer to Byzantine models of the Ravenna mosaics of Saint Apollinare in Classe the choice of iconography and the general setting. The Crucifix is a replacement of the older one, restored in 1910, which popular tradition believed was miraculous since it was carried in procession by Saint Charles Borromeo during his pastoral visit in 1570.

The organ, situated on the wall above the entrance, dates back to 1888 and was made by the Bernasconi factory. It was adapted in 1910 by the organ builder Elia Gandini of Varese. In the following gallery: the facade, the side elevation and apse, the interiors and the Black Madonna. Photo www.wikipedia.org

Actual structure

The current layout dates back to 1911 and was consecrated by Cardinal Ferrari. Indeed, the church has undergone many structural interventions, including a complex restoration started in 1897 by the Gallaratese Society for Patri Studies that was overseen by the Regional Office for the Conservation of Monuments of Lombardy.

The external works concerned the elimination of the buildings leaning against the side. Also, the demolition of the bell tower, the continuation of the loggia of arches built on the base of the existing ones, the enlargement of the apse in the shape of a semicircle on the existing hexagonal one, and the modification of the large window of the facade with a rounded Baroque decorative style. Inside, the masonry vault was transformed into a ceiling with wooden beams, while a terracotta floor replaces the old Venetian mosaic floor.

Last restoration

In the 1960s, again under the responsibility of the aforementioned Society, excavations were carried out near the apse. Bringing to light several tombs with some grave goods (items buried alongside the deceased), now kept in the Museum of the Gallarate Society for Patri Studies. The last restorations were carried out in the eighties by the architect Francesco Moglia.

In previous centuries, the structure experienced a series of historical and social vicissitudes that led to structural changes and changes in use, including non-religious functions, due to poor management of the structure by the Lomeno family, a noble feudal family of the Visconti, who, in 1368 obtained the patronage of the church from Gian Galeazzo Visconti. The name of the Lomeno family appears in a deed dated 1364 concerning a bequest by a member of the family for the celebration of mass. From the beginning of the 15th century, the structure experienced a religious and artistic decline and, during the period of war, was transformed into a fortress complete with typical medieval battlements and a moat, to defend the population in the event of danger.

Meeting place

Following the destruction of the Town Hall building in 1499 by the Swiss and the Milanese, it also became a meeting place for city affairs. The appearance of the church was significantly altered when houses were built against the side including a butcher’s and a carpentry shop with access into the structure itself. In 1566, the massacre of the church was now complete, so the Apostolic Visitor Lionello Clivone ordered the suspension of all religious functions.

Thanks to the intervention of San Carlo Borromeo, who, in 1570, ordered that the building be returned to its original purpose and indicated a series of changes to be made, the Lomenos had no choice but to comply. However, only in 1657, by order of the Provost Giulio Moneta, were the requested modifications carried out, including the movement of the off-centre entrance to the right and the modification of the large window of the façade, lending to the church that Baroque aspect which was preserved until the end of the works, that is until the late 1800 – early 1900s.

Notable archeological interest

The church of San Pietro has aroused considerable archaeological interest due to the presence of ancient relics such as a Roman Corinthian capital of acanthus leaves, recovered during the excavation works at the church house of Arnate, a fraction of Gallarate, and which was used as a holy water font. Since 1911, the relics of Saints Onorato and Fortunato have been kept in the altar, while the tombs found during the archaeological excavations of the 1960s are on the floor against the wall.

The church acquired considerable importance in the 19th century as a place of celebration of the funerals of the most important personages of the time, and thanks to its being nominated as a National Monument by the newly born Kingdom of Italy. The church of San Pietro was also visited by Theodor Mommsen, who was considered the greatest classicist of the 19th century and recognized for his important studies on the history of ancient Rome. In the 1900s, thanks to lithographs by Adriano Porazzi and numerous celebratory postcards, it became an icon of Gallarate.

Crocetta in piazza Libertà, 1694

On the side of the church of San Pietro there is a column called Crocetta or “Cruzeta” in dialect, in homage to the iron cross placed on its top. It is a Christian symbol very dear to the people of Gallarate and a symbol of the city as the only and last attestation of the feudal period of Gallarate. It consists of a stone pedestal upon which is a long column that ends with a capital holding a double-sided high-relief representing the Virgin Mary with the child – “Our Lady of the Pillar” venerated in Zaragoza – with an 18th-century cross on top.

Initially, the column was placed in the center of the square and was later moved further along the main road. In fact, its current position dates back to the beginning of the 1900s when the monument was placed next to the church of San Pietro, as if to protect it, in place of the buildings demolished by all the restoration work carried out.

Cesare Visconti

The column was erected in 1694 by Cesare Visconti, Feudatory Count of Gallarate when, in honor of the Virgin Mother, he obtained the privilege of the title of Grandee of Spain of the fiefdom of Gallarate, which was a first in Lombardy. During the Spanish era, it was the custom to build statues and tombstones, and in honor of his award, he had emphatic inscriptions in Latin engraved on the base, all now illegible.

In 1908, the Società degli Studi Patri took steps to make the writings on the pedestal legible again through the creation of a plaster cast, and the result of this procedure was published in the Rivista Periodica Sociale of 1909. From these writings we read that Count Visconti had the smaller existing column built in 1530 by Cardinal Marino Caracciolo, who, in recognition of merit, was given the title of Count of Gallarate and Feudatory of the Village by Duke Francesco II Sforza. This more modest version was transported to Milan and subsequently demolished in 1845. Other inscriptions bear the phrase: “Posterity should judge the Author, the thing, the end, the way, the time”.

French invasion

During the French invasion between 1796 and 1798, the Crocetta survived the attempt to place a statue of “Liberty” on its top in place of the cross, an attempt which the majority of the population opposed. In 1825, the then Municipal Administration attempted to demolish the column or to transfer it elsewhere, to make the square more spacious and open to wider market development, but the provost Carlo Ambrogio Curioni opposed it and with the support of the population, it remained untouched. From a symbol of feudal power, the Crocetta has has become for the people of Gallarate a prevalently religious monument representing the defence of the Catholic faith and the nourishment of the piety of the faithful. Photo www.liceogallarate.edu.it

Palazzo del Broletto in via Cavour, XIII century

From the central square, continuing along Via Cavour, is Palazzo Broletto. This building has very ancient origins and was born in the 13th century as a convent attached to the church of San Michele which was demolished between 1859 and 1961 during renovations by the architect Leone Savoia. The religious building was built by the Humiliati monks in the 13th century and was characterised by the production of mulberry trees. It was also the center of an important Saturday market.

It then passed to the Benedictine and Augustinian nuns who held it until 1784 and was finally given to the Franciscan order of Friars Minor. Under the short-lived French government, it was destined to become the seat of the Municipality of Gallarate, and the first solemn public session was held there in 1799. In 1803, the Municipality of Gallarate also housed a public schools for boys and the weekly cereal market. It was the seat of the District Court, the prisons and other offices. Today, it is the seat of part of the offices of the Municipality of Gallarate.

Courtyard

The building retains its rectangular plan with the large internal courtyard with a cross-vaulted portico. While, the facade is in neoclassical style, with two large symmetrical entrance doors. The surface is covered in smooth ashlar stone and is punctuated by arched windows, pilasters and a belt course frame. The internal courtyard has been recently renovated respecting the original historical architectural principles. Photo www.varesepolis.it

As already mentioned, immediately after the mid-1800s, in the years between the events that led to the unification of Italy, there was increased economic growth, contributing to the first phase of industrialization, During this time, Gallarate underwent an important period of development which affected every aspect of civil life, the economy and of urban planning which was characterized by much enthusiasm and a desire for expansion.

Thanks to one of the most important Lombard industrial families of the time, many notable architectural projects were carried out, including the civic hospital, the expansion and relocation of the Monumental Cemetery to its current location, the construction of the municipal kindergarten, the first Technical School, and general improvements to living conditions. In fact, the textile industrialist Andrea Ponti, leader of the Municipality in the first elections of the new Italy in 1860, promised the financing of a series of works of public importance that would bring wealth and prestige to the city. For some of these works, he would rely on a much appreciated Milanese architect: the architect Camillo Boito.

Camillo Boito architect

Born in Rome in 1836, Boito died in Milan on June 28, 1914. At the age of fourteen he began to follow courses at the Academy of Fine Arts in Venice and, in 1860, was invited to fill the position of professor of architecture left vacant by F. Schmidt, one of the greatest exponents of the neo-Gothic style, and held the chair until the beginning of 1909. For forty-three consecutive years, he also taught at the Milan Polytechnic. Among his most important projects are the Giuseppe Verdi Rest Home for Musicians in Milan and the Palazzo delle Debite in Padua. He became a leading figure in the debate that animated the Italian artistic world in the aftermath of national unity, around the search for the “national style”, which was thought should characterize the architecture, painting and sculpture of the newly established Kingdom of Italy.

He stated that the study of the classics should be considered the destination and not the starting point in artistic research, and identified the guidelines of the new Italian style within the context of Eclecticism and Neoclassicism. The “fundamental issue” for Boito was to identify what he considered the fundamental components in architecture: the organic part and the symbolic part; the former constituted by the framework, the logical and rational part for the distributive and functional characteristics, and by structural and material qualities, while the latter expresses the artistic and aesthetic qualities “with the indefinable spirit of art”.

Philological restoration theory

He also defined the dictates of the so-called “philological restoration”, still a reference point today for the current restoration, i.e. the recognizability of the intervention, respect for the artistic additions made over time, and protecting the signs of the passing of time. In his narrative, the constant of the theme of beauty is evident, developed in all its forms – architectural, musical, artistic and even literary; in fact, he participated in the literary movement of the Scapigliatura, the Milanese equivalent of the Parisian Bohemian movement. Elected councilor, Ponti kept his electoral promises. Thanks to the generosity of these characters who had the destiny and prestige of their hometown at heart, we can still enjoy many wonderful works which merit our respect, both for the artistic accomplishments and the men behind them.

Funerary chapel of the Ponti family at the Monumental Cemetery in viale Milano by the architect. Camillo Boito, 1865

On 23 April 1864, following a cholera epidemic, the City Council approved the construction of the new Monumental Cemetery and the Ponti family was granted the free acquisition of land for their family mortuary chapel. Camillo Boito was entrusted with the entire project of the new cemetery which was one of the first urban “rationalizations” resulting from the 1890 “improvement plan” of Engineer Marino Croci.

The project was characterised by a “constructive sincerity” that Croci himself had explicitly referenced in his writings of 1867: “…or the style of the Cemetery [of Gallarate] is all frank, all friendly to truth: the materials are what they seem; there is no cement or stucco…”. Basically, the architectural complex included two different linguistic registers, each with its different choice of materials, one between the wall enclosure with pure forms in the neo-Romanesque style with expressive elements of neo-Gothic taste, and the more monumental central style for the Ponti family located in front of the entrance towards the back. The former includes constructions with exposed brick walls in which the architectural decoration consists of simple motifs that enhance the compactness of the wall mass.

Front side

On the front side, each chapel has a simple entrance portal flanked by two raised columns with bases and capitals in Angera stone, supporting a round masonry arch, inscribed in a dentilwork cornice. The first two buildings next to the entrance, built as an oratory and private chapel and featuring a decorated cross that stands out on the cusp roof, have more marked decoration due to the presence of a frame in Angera stone around the arch placed above the entrance doors. A more elaborate and monumental style is instead used for the construction of the majestic Ponti chapel in Angera stone.

The main chapel of the cemetery, raised from the ground, was built following a Greek cross plan which provides, in the corners of the square in which it is inscribed, four cells over 150 columbarium, intended for burials. In the apse is the staircase to access the basement. The chapel ends with a dome with an octagonal base which is in turn surmounted by an angel, the work of Edoardo Tabacchi. Along the perimeter of the cemetery, on both sides, there are chapels with numerous Art Nouveau elements in wrought iron, dedicated to the most famous families and worthy personalities of Gallarate. Photo www.fondoambiente.it

Hospital of Sant’Antonio in Largo Camillo Boito by the architect Camillo Boito, 1874

In 1869, the architect Camillo Boito also designed the civic hospital for Gallarate, whose construction was completed in 1874, and which reflected a mature style. The imposing structure is considered one of the most symbolic buildings of post-unification Lombard architecture due to the original use of materials such as plastered stone, smooth Angera stone, white granite and exposed brick, and also the ornamental emphasis of the entrance with staircase, porch, elegant three-mullioned window and tympanum, and for the layout of the internal sanitary spaces.

This three-wing building has two floors, and features original details in the facade decorations and stained glass windows. The Hospital has a horseshoe layout, for greater exposure to the wind to avoid stagnation of miasmas, and is slightly rotated with respect to the east/west axis to ensure all rooms enjoy sunlight. On the ground floor, there were clinics and offices in the central body of the building, and laterally, two floors housing infirmaries and 44 beds (24 for men and 20 for women).

Central body

On the first floor of the central body were the residences of the doctors and nuns, while the kitchens and mortuary chambers were situated in the basement. Inside, a corridor runs around the courtyard, serving various rooms both on the ground floor and on the first floor. In the first phase of construction the project was not built in its entirety; only in 1911 was the construction of the left wing completed.

At its opening, the hospital did not have operating rooms and in 1933 the structure was not considered suitable to contain surgical services, therefore the pavilions were readapted to accommodate less sensitive services. In 1943, the hospital was militarized, this lasting until 1945. Over the years, the hospital complex was refined and while the Boito pavilion could be said to have lost technical importance, it retained its administrative and urban relevance. Restorations were carried out in the 1970s. Today it houses general outpatient clinics with the psychiatry department on the first floor and general offices on the ground floor. Photo www.wikipedia.com

At the turn of the 1800s and 1900s came the second period of great awakening called the “Belle Epoque” which originated in Europe, particularly Paris, and which then spread to the rest of the world. This new global movement affected art, culture and society through a newfound desire to live and was pervaded by a feeling of optimism towards a future offering peace and well-being thanks to the progress of science, technology and civilization.

Liberty style

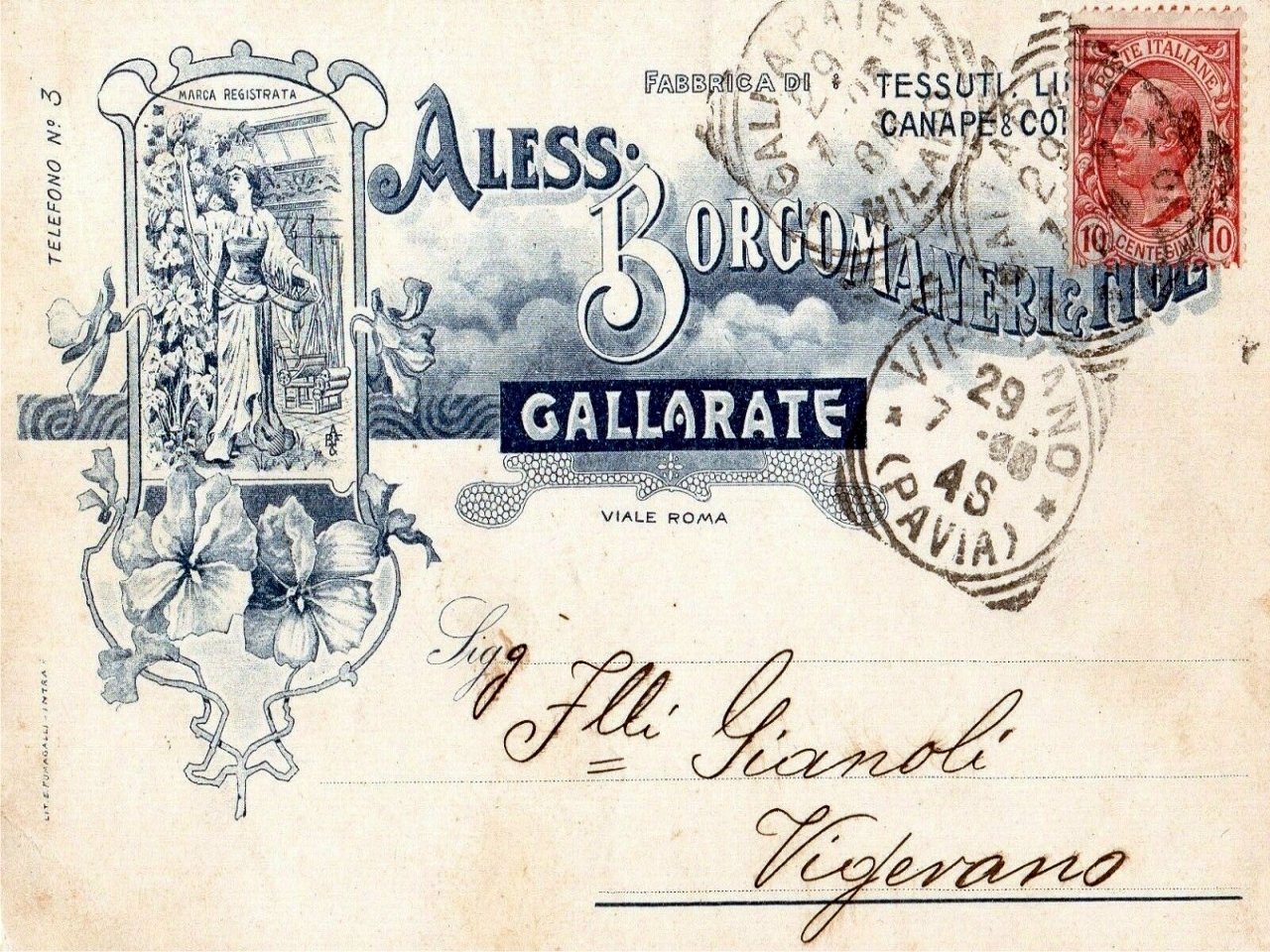

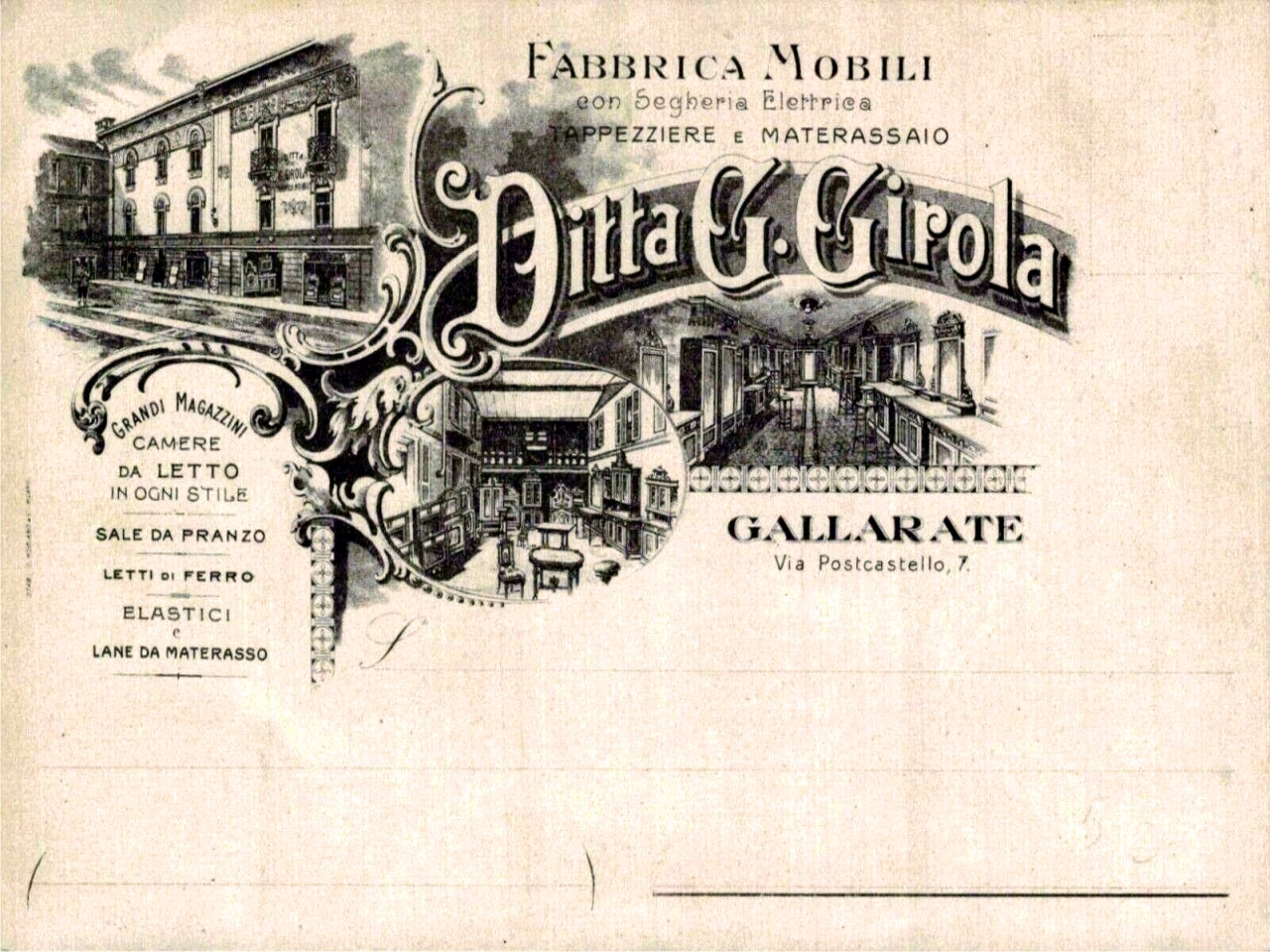

In this context, Gallarate saw a new phase of industrial expansion. The floral fashion introduced by the “Liberty” movement in architecture, furnishings and fashion also spread to influence the typography and lithography of posters, billboards, book covers, almanacs and more.

As far as architecture is concerned, particularly in the early 1900s, this new artistic movement left its mark in Gallarate, especially in some areas of the city. Industrial development led to demographic expansion and made a new Master Plan necessary. The concentration of evidence of the Liberty style north-west of the town’s historic center is linked to the Master Plan of Giovanni Massera, who, in 1880, prepared that area for the development of the new urban center following an octagonal plan typical of the nineteenth century. Milan was the propulsive center of Lombard Liberty, in Varese the relationship with the lake and the mountains and exchanges with Ticino defined its own style, while in the provinces, style was adapted to local taste. Clients were members of the upper middle class and of Case e Alloggi, one of the few real estate agencies in the area at the time.

Filippo Tenconi and Carlo Moroni architects

The studio of engineer Filippo Tenconi and architect Carlo Moroni was that most frequently used for the design of new residential homes, family tombs and industrial warehouses, and used the canons of the new Liberty style. First this was visible in friezes, volutes and floral decorations, later in complete buildings following the typical structure of a two-story villa with a belvedere turret. The characteristics of Moroni’s style were the use of ashlar in the lower part, and rough plaster in the upper, following the static truth thesis of the architect John Belcher, according to whom «to obtain a sense of solidity, the lower part of the building must show greater consistency than the upper part.»

In its various forms, Moroni established two strong ties from an artistic point of view. The first with the city of Milan in its function as a cultural, economic and social center. While the second was with the architect Camillo Boito, known for the construction of the new hospital, who influenced him in the use of exposed brick, decorative bands that break up the walls, and details reflecting the Lombard tradition. In his various ornamental experiments, his vision was characterised by a more simplified liberty style compared to the that which developed in Milan, and was evident in the lack of majolica on the facades, of putti or figures of women or female heads, while the internal walls were not covered with flowers, and the handrails and railings unembellished by roses or irises.

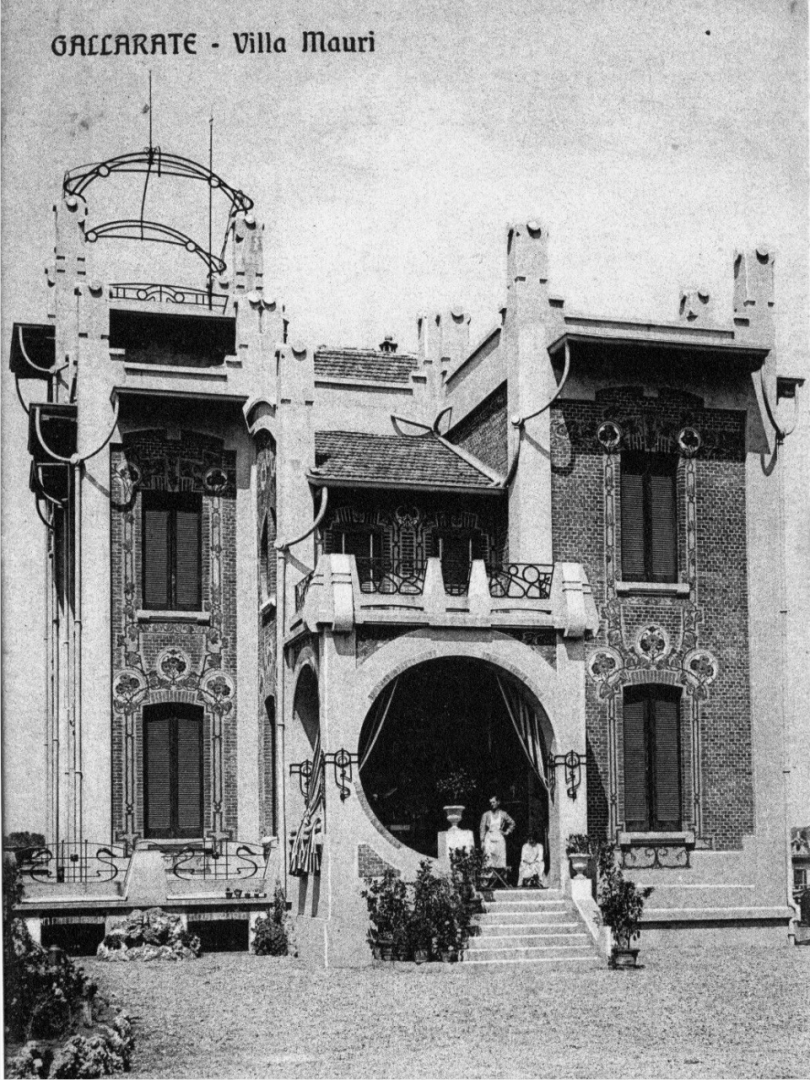

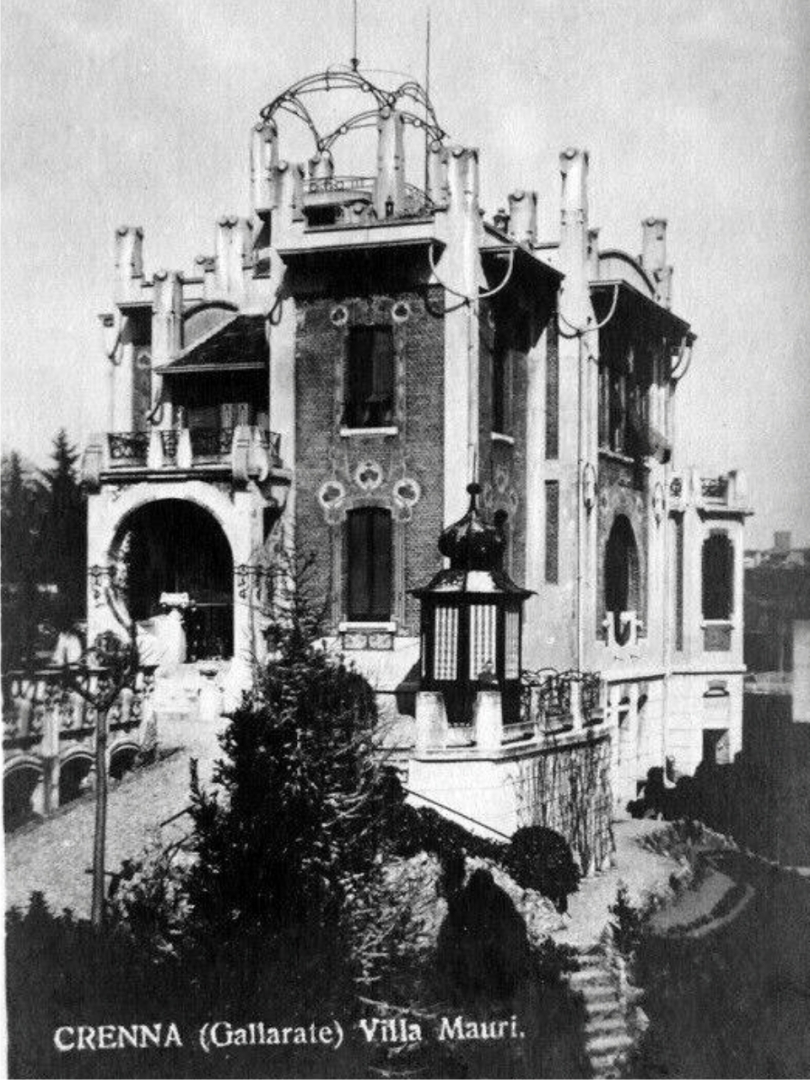

Villa Rodolfo Mauri in via Solferino, architect Carlo Moroni, beginning of the 1900s

The Villa Rodolfo Mauri, commissioned to the architect Carlo Moroni by the then mayor of GallaratRodolfo Mauri, offers a suggestive glimpse into the Gallaratese architectural panorama. It is undoubtedly the best example of Liberty style designed by Moroni, for its broken and sinuous shapes, the knowledge of the distribution of the Ron accents, the circular three-mullioned windows with coloured glass, and finally for the effect created by the colour contrast of the materials.

The construction of the irregular plan raised by open arches has elevations showing contrast between the exposed brick, the light plaster that frames the various bodies, and the cement decorations on the openings. While, the entrance is characterized by a circular opening surmounted by a balcony surrounded by splendid ironwork, overlooked by two rectangular windows with a concrete and brick frame. Finally, the circular opening is also repeated on the rear side, creating a window that illuminates the hall on the ground floor. Finally, the side elevation shows a turret opened by two circular mullioned windows.

Decorative ironwork

The villa is situated at the end of a sharp bend on the top of the slope leading towards Corso Sempione, and is slightly hidden by the fence of Villa Rosa dei Bassetti. Arriving near the building, one is struck by the wall enclosure characterized by a series of columns in relief with worked capitals, and decorative ironwork with naturalistic motifs, also visible in the two striking gates.

During the renovation, many decorative elements were removed making the final effect cleaner, but which nevertheless retains its liveliness. Photo www.art.nouveau.world

Carlo Bassetti weaving mill in via Novara by the architect Carlo Moroni, from 1905

The Carlo Bassetti weaving complex – founded in 1875 and still in full operation today – designed by Moroni, is considered one of the greatest examples of Liberty style in the province of Varese. Overlooking the street, it is an elegant structure with buildings that house the concierge and offices. The facade offers chromatic contrast between the plaster, in the colours of yellow and brown, and the white of the decorative stuccos and the commercial coat of arms in perfect floral style. The design of the façade is enlivened by the three decorated lowered arches in the mouldings, the five mullioned windows on the first floor and by the two lateral bodies featuring ornamental mullioned windows. Photo www.tessituracarlobassetti.com

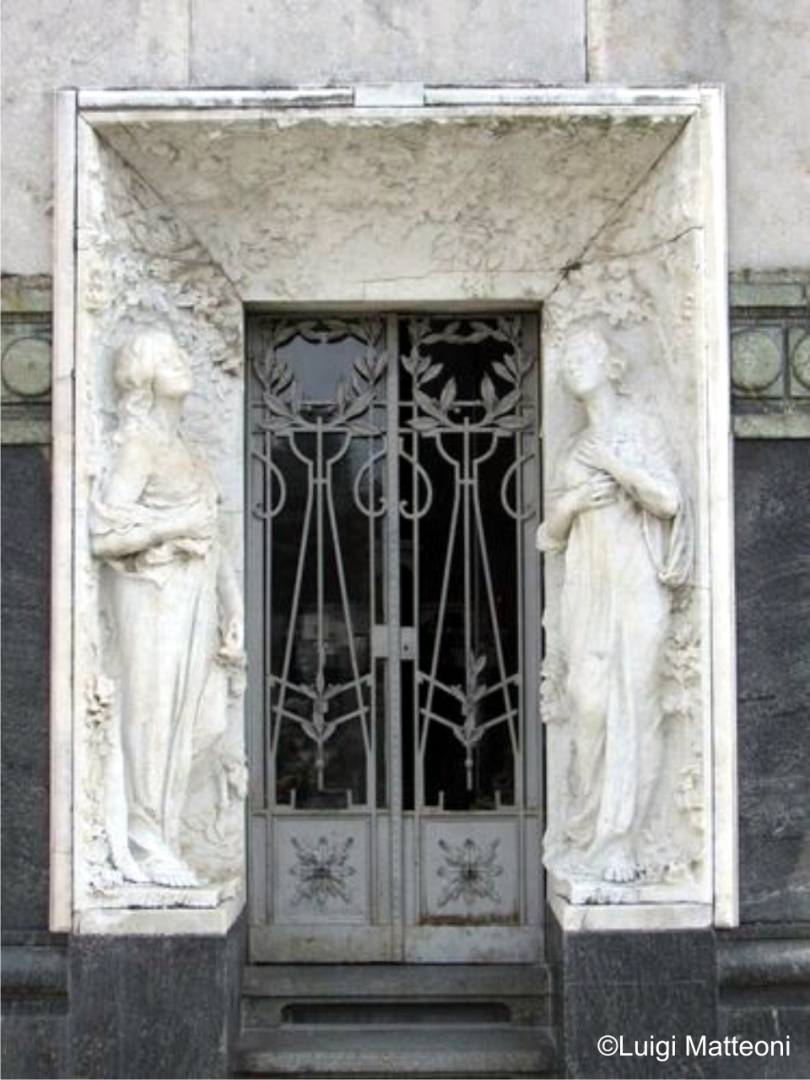

Funerary art

Of particular importance is the funerary art expressed by sculptors such as Eugenio Pellini, Edoardo Tabacchi, Enrico Rusconi, Vittorio Tavernari, Luigi Bennati, Renzo Colombo, Umberto Franzosi, Giuseppe Maretto, Gottardo Freschetti, Alberto Dlesser and Adolfo Wildt, with its poignant carved faces full of pain. Known for his works in the Monumental Cemetery of Milan, Wildt is considered one of the major exponents of sculpture from the Liberty period for his works characterized by masterful technique and profound symbolism. Some of his bas-reliefs are exhibited in the Studi Patri museum.

In fact, the Monumental Cemetery houses numerous tombs and works attributable to the Liberty style, which through funerary art achieved masterpieces of perfect architectural and sculptural synthesis. Here we see female figures in prayer with recognizable elements in the clothing and a wealth of flowers, or figures of women in a sorrowful attitude and floral ornaments, or columns and oriental details. Photo by Luigi Matteoni www.instagram.com/luigi_matteoni

The First World War slowed this evolution down but many examples of local expression of the style of the period remain. The 1920s continued to see many changes in buildings in Gallarate – this before the 1929 economic and financial crisis that began in the USA and which later slowed things down drastically. In the space of a decade, some valuable urban buildings were created, such as the Crenna stairway, the Casa del Balilla, later destined to become the civic library, and the “Liberty stairway” of the station. It was also an auspicious period for private construction. In those years, the floral style of Art Nouveau modified the organic and fluid shapes into more geometric and elegant lines, resulting in the style called Art Decò.

Villa Orlandi or the “stone house” facade of the architect Giulio Ulisse Arata in Piazza Guenzati, from 1929

In 1928, for the renovation of the facade of the large Orlandi house on the side facing Piazza Guenzat, Annibale Orlandi, from the well-known family of textile industrialists from Gallarate, decided to entrust the task to the architect. Giulio Ulisse Arata. Arata was originally from Piacenza and was active mainly in Milan, Naples and Bologna. The result was a majestic building with distinctive and original shapes, marked by the monumental strength of white Aurisina stone, but also by the asymmetry of the decoration of the tympanums and trabeations, and by the elegance of the top floor where there is a large frescoed covered balcony. The sides of the facade have different facings: on the left there is a smooth ending in a high double triangular pediment, while the right side is partly in stone in relief and has a broken tympanum.

All the vicissitudes of the construction of the facade intersected with the history of the central station of Milan. In fact, the construction site started in July 1929 and ended only three years later; the delay was caused by the fascists ordering the Milano Centrale station project to speed up, as it was a project that had been open for at least two decades. Mussolini diverted the use of the Aurisina stone to the construction of the gigantic Milanese railway station, thus slowing down the supply of materials to other construction sites.

Giulio Ulisse Arata architect

The architect Giulio Ulisse Arata (1881 to 1962), attended architecture courses at the Brera Academy of Fine Arts from 1898 to 1901. So he was influenced by the architects Camillo Boito and Luca Beltrami. He immediately showed interest in the Art Decò movement and defined his personal style which was characterized by the skilful contamination of several styles of Modernism influenced by classical taste. This style was renowned for its skilful use of stone and worked concrete represents the end of the Liberty period, above all in Milan. Among his best-known works are the Palazzo Berri Meregalli in Milan and the elliptical staircase at the Palazzo Mannajuolo in Naples. Photo www.varesenews.it

The architects of the 2000s are faced with the need for an architectural and urban planning approach based on the desire to complete the urban grid of the city’s significant buildings, while retaining a certain continuity with the styles already present in the areas designated for new construction, notwithstanding the addition of modern and technological elements related to energy efficiency that new housing requires.

Residential tower in the former Cantoni area in Piazza San Lorenzo by the architect Mario Botta, 2016

Swiss master Mario Botta, founder of the Ticino school and one of the most important names in the world of architecture, has chosen Gallarate as his only project in the whole province of Varese. Actually, the project is part of the integrated municipal intervention plan, aimed at giving a new identity to the former Cantoni industrial area demolished in 2006.

The prestigious firm and Studio de Risi have created a high energy performance residential tower intended to house homes, offices and shops through the partnership between the architect Mario Botta and Ondulit Italiana (roof manufacturer). Generally, the predominant characteristics of the collaboration are the skilful use of large glass surfaces both in commercial activities and in residences, with the aim of making the most of the use of natural light and enjoying the fascinating panorama, especially from the higher floors where in certain favorable weather conditions it is possible to see Monte Rosa. Furthermore, they make good use of exposed brick, which recalls the architectural style of the local urban surroundings; in fact, overlooking Piazza San Lorenzo is another structure with exposed bricks built in the Fascist era, which is now used as a library.

Multifunctional complex

An unmistakable architectural style, which brings to mind the multifunctional complex at the former Appiani in Treviso, is made even more particular by the presence of a curved roof on which a latest-generation solar panel system has been built. The “eye”, which is formed by the union of two curved surfaces, is Botta’s signature element. In general, the complex consists of three buildings, one being a central tower that is eight-floors high, and two others adjacent to the tower and rotated by 30°, almost forming a C shape, which extend in a line with three floors above ground. The ground floor is dedicated to shops, the first and second floors to offices while the remaining five floors above ground house the residences.

Mario Botta architect

He enrolled in the faculty of architecture in Venice where he met Le Corbusier who was in Venice to build the hospital, and with whom he began to collaborate. Botta graduated with Carlo Scarpa from whom he would take the concept of artisanal materiality. The architect is known internationally for projects such as the San Francisco Museum of Contemporary Art, the Mart in Rovereto, the Cymbalista Synagogue in Tel Aviv, the Jean Tinguely Museum in Basel and the Tokyo Art Gallery. Photo www.candelacostruzioni.it

The work of new designers sometimes becomes a “typical Italian” affair where a mix of negligence, bureaucracy and an ambiguous approach result in controversy and a long series of acts and projects in the political-judiciary sphere that lasts for years. This is the case for historic buildings not listed as monuments that are demolished, for structural and safety reasons according to some, as an act of disregard for historical heritage according to others. A dead end from which Gallarate recently emerged, giving permission for the construction of modern residential buildings in an area near the center where an old Art Nouveau building once stood, in exchange for having a prestigious designer carry out the works.

Residential complex in via Roma by the Portuguese architect Alvaro Siza, 2020

Coming from the center and continuing along via Roma, one is surprised by this imposing structure made of travertine slabs that sits on this very busy road and which was completed in 2020. This recent high-end residential complex was designed by the Portuguese architect and 1992 Pritzker prize winner Alvaro Siza, along with the architect Roberto Cremascoli of the Studio Cremascoli Okumura Rodrigues Arquitectos, who is Italian but Portuguese by adoption, and stands out for its rigorous lines devoid of any decoration or contrast in colours or materials.

This small-scale intervention (19 apartments for about a total of 11,000 cubic meters) is very interesting as the complex is made up of two structures that reinterpret two different types of residential buildings: the courtyard, very much part of the urban fabric of western Lombardy, and the villa. The two types of dwellings are combined here for the difficult task of speaking a single language.

Alvaro Siza project

Basically, the project attempts to achieve an urban complexity capable of undermining the principles of isolated buildings, instead emphasizing relationships with the surrounding context through the creation of physical and perceptual relationships, paths and guidelines. The complex has two main bodies situated on the road that connects the central Piazza Garibaldi with Via Roma: the two buildings become an integral part of the stratified morphology of the consolidated urban fabric, with a typological system designed to lend importance to external spaces, to public and private routes, and bring back the courtyards and alleys of the centre. All of this without compromising the formal and compositional quality of the buildings which, with their series of deep loggias and balconies, contribute to an extremely topical urban and civil architecture.

To accompany the planning from the beginning, which was in 2012, was the visit to the cornerstones of Milanese architecture: from Asnago and Vender to Gio Ponti, from Ignazio Gardella and Piero Portaluppi to Aldo Rossi. After the Venetian experience on the island of Giudecca, the Portuguese architect tried his hand here in Gallarate with another residential project, a sector where he left his mark on some of the most extraordinary pages of twentieth-century European architecture, such as the adventure of the SAAL Brigades (Serviço de Apojo Ambulatorio Local), exactly 40 years ago, in northern Portugal. Photo Francesca Ióvene. In terms of monuments, the city of Gallarate has not forgotten the ultimate sacrifice offered by its young people during the two world wars or in the Nazi extermination camps.

Monument to the fallen in Piazza Risorgimento by Enrico Butti from 1924

A monument to the sacrifice offered by our young during the First World War, this work was conceived by the architects G. Mainetti and F. Tettamanzi of Milan and includes sculptures by Enrico Butti. More than once, Butti took on this specific type of monument, which was very widespread in the years between the two world wars. Other examples in the province of Varese can be found in Viggiù and Varese. The interpretation of the theme of the male nude is evident in his. works, in an emphasized Michelangelo style that transpires in the expressiveness of the faces, with fluid movements and anatomical perfection.

Enrico Butti

He (1847 to 1932) was a sculptor and painter who left important works in the province of Varese and Milan where he arrived in 1861 to attend the Brera Academy of Fine Arts. He was born in Viggiù in the province of Varese into a family of traditional marble artisans; at the National Exhibition of 1872, he exhibited one of his first works, the marble by Raffaello Sanzio, and in Brera, two years later, his work Eleonora d’Este Going to Visit Torquato Tasso in Prison, which is today in St. Petersburg.

Butti created works for Milan Cathedral and for the Monumental Cemetery, also the monument of the Lombard warrior Alberto da Giussano di Legnano, and The Miner, which earned him the Grand Prix and the silver medal at the 1889 Paris International Exposition. The artist also created many other celebratory monuments for Milan such as that of General Sirtori in the Public Gardens and the monument to Giuseppe Verdi in Piazza Buonarroti.

The monument

It’is structured following a fairly traditional layout, and is grandiose and forceful. It consists of a high pedestal, flanked by two ares, from which rise two honorary columns ending with two torches. The central sculptural group, placed high on a high granite base, immortalizes a wounded soldier surrounded by other soldiers. It should be noted that of the two figures on the sides of the base of the monument, the male, on the left, is an exact copy taken from the statue of the Lookout from the group The Truce of 1906.

The female figure is also clearly inspired by the work. Further up between the two columns are two putti. The statues at the base are life-size while, in order to offer perfect perspective, those at the top are larger, so the whole gives the impression of a perfect 1:1 scale. The architectural structure of the monument is in polished red Baveno granite. During 2007-2008, the War Memorial of Gallarate was moved from Piazza Risorgimento to allow for the restoration of the monument and the redevelopment of the piazza, after which it was put back in place. Side photo www.catalogo.beniculturali.it

Monument to the Resistance by Arnaldo Pomodoro in Largo Camussi from 1980

The need to dedicate a monument to the Resistance arose in 1979 after the discussion between political forces and the partisan associations of the city in acknowledgment that, 34 years after the Liberation, Gallarate had not yet dedicated a work of high moral value to this historical moment and its values of freedom, justice and democracy.

The director of the Civic Gallery of Modern Art, Silvio Zanella, contacted more than 200 artists, galleries and critics to compile a shortlist of artists from whom to request a proposal. Many of these artists came to the city to see the location and the context in which the work would be placed. In the end, the 41 artists who were contacted presented a total of 69 projects or work hypotheses which were displayed in an exhibition open to the town’s citizens. Among the artists contacted were, Andrea Cascella, Pietro Consagra, Fausto Melotti, Floriano Bodini, Marcello Morandini and Vittorio Tavernari.

Arnaldo Pomodoro

After a spirited evaluation, the commission in charge of choosing the work chose Arnaldo Pomodoro’s “Movement of collapse” of which four copies were made between 1970 and 1971: the other versions are located at the Banca Popolare di Milano in Milan, in the artist’s collection and one in a private collection. Perhaps the most obvious quality in Arnaldo Pomodoro’s work is the public vocation of his works. His sculptures adorn important cities such as Rome, Milan, Turin, Copenhagen, Brisbane and Dublin and can also be seen in the Cortile della Pigna of the Vatican Museums, in the Kremlin and at the UN. From a fountain seen to bathe and wash the contortions and cracks of life, this great monument bears the marks of history as well as the those left by the hand of the sculptor.

Indeed, as with Pomodoro’s famous bronze spheres (bronze being his favorite material), the surface breaks and tears apart in front of the viewer, who is led to search and discover the internal mechanism of the sculpture, which seems to aspire to freedom. Right from the start, his reliefs celebrate an independent, spontaneous creativity, but are nevertheless imbued with a certain archaic sacredness deriving from the references to classical sculpture. The rigorous geometric spirit that dominates Pomodoro’s art pushes every form towards the volumetric essentiality of the perfect solid that is cleanly cut or torn.

Sense of falling

The outer space seems almost not to exist; the almost mirror-like smoothness of the exterior is counterpointed by the complexity of the interior made of thorns, nails, intricate and twisted barbs. All the action takes place inside, in the bowels enclosed in the smooth, clean walls. The central rift expresses the sense of falling, or rather of collapse, as the title also spells out. A deep open wound, a laceration that can no longer be closed, a ragged rip. The height of the work at over five meters and its upward momentum makes the work particularly striking.

Last restoration

Pomodoro’s monument has been returned to its former glory thanks to the 2015 restoration carried out Agostino Ragusa, a craftsman requested by the sculptor himself to carry out maintenance work. The patina that had made the monument dark and opaque was removed and it was also cleaned and polished. Also, was repaired the basin which had developed leaks. The costs of the operation were covered by a loan obtained in November 2014 from the Municipality of Gallarate, in collaboration with the MA*GA Museum, thanks to participation in a regional invitation to tender dedicated to the enhancement of cultural heritage. Photo www.varesenews.it

For the description of other buildings of historical and artistic interest, refer to the map inserted at the end of the previous section where, however, not all the most important places in Gallarate are indicated, but only those selected to feature in the collection’s advertising campaign. In a country like Italy where beauty is widespread, it would be an arduous task to provide a complete list on internet.

I leave it to the reader to choose his own favourite place. The level of sensitivity of places is a subjective concept, but at a Municipal Administration level it is identified by integrating historical documentation and evaluating landscape components in terms of relevance and integrity with systemic landscape and symbolic evaluation criteria. The recognition and cult of memory are fundamental elements for a city that looks towards the future, as demonstrated by the museum system of Gallarate.

Museum of Patri Studies since 1896 in the Franciscan cloister of 1234

The Gallaratese Society for Patri Studies is a private organization founded in 1896 by a group of young people passionate about local culture, spurred on by Ercole Ferrario, one of the most important intellectual figures of the 19th century in Lombardy, with the aim of safeguarding, protecting and enhancing the cultural heritage of the city of Gallarate and the Upper Milan area.

The activities carried out also included the promotion of restoration and archaeological research in places of interest, and also the study, restoration, cataloging and analysis of the finds and publishing them through the printing of periodical publications, the organization of cycles of conferences and conventions, and the opening of its own exhibition center. Initially the Museo degli Studi Patri was located in Palazzo Broletto, but in 1911 it was inaugurated in the current location following the restoration promoted by the real estate company “Case ed Alloggi Macchi & Co” belonging to Enrico Macchi, the architect who, in 1926, donated the property to the society itself.

Ancient Convent

The Museum is located in what remains of the ancient Convent of San Francesco built just outside the walls, on the road to Varese and Switzerland; it has an internal porticoed courtyard supported by slender sandstone columns with capitals and pointed arches. After the first restoration, subsequent interventions were carried out by the Superintendence of Architectural and Environmental Heritage of Lombardy with funding from the Ministry of Cultural Heritage. The intricate Franciscan complex was built in 1234 by Leone da Perego, provincial minister until 1241 and later, eight years after the death of St. Francis, the Archbishop of Milan, in order to strengthen the presence of the Order of the Franciscan Friars Minor in Lombardy.

As the eighth diocese of Milan, the complex of buildings included the Church, built with striking colours due to the use of terracotta masonry, and with interiors with ribbed cross vaults in terracotta and Gothic stone keys and bare walls in light plaster, subsequently enriched with frescoes and coloured stucco friezes. Adjacent to the Church is the convent with two identical rectangular cloisters placed axially, with the main side parallel to the Church. Subsequently, in 1936, the religious building, now dilapidated, was demolished to make way for the construction of a cinema, while the area was divided between several owners.

Only the southern part of the northern cloister, which was orthogonally intersected by the current via Borgo Antico, was endured. In 1967, during the excavations of the ancient church, many findings were made including the floor, skeletons in masonry niches and in the mass grave, the remains of a cantharus, a miniature well with a wooden barrel at the bottom and other architectural elements as well as other findings that were conserved in the museum.

A Franciscan cloister

The Franciscan cloister is classified as a historical architectural monument of particular interest, not only for being one of the few oldest buildings in Gallarate, but also for the importance that the building had in the town’s history, as stated in the Archbishop’s of Rouen’s report in 1254, and due to the fact that, in 1355, the Duke Galeazzo Visconti ordered the friars to preserve the juridical and administrative documents. Further confirmation of its importance is the evidence that members of particularly important families were buried in the area of the church of San Francesco, such as Ottone Orsini from Cedrate in 1309 and Ugo from Laveno in 1322.

The archaeological-historical collection on display is made up of the results of archaeological research promoted by the Società degli Studi Patri in the Gallarate area and in the foothills between the Ticino and Olona valleys, and by the bequests of the most important families of Gallarate. It has grown and flourished over time to such an extent that it has consolidated its role among the oldest and most worthy local and national institutions, in the cultural field of research and study of the Antico Seprio area and in particular of the “Golasecca civilization”.

Giovanni Batista Giani

Since 1976, an epigraph in Candoglia marble has protected the remains of the aforementioned abbot Giovanni Batista Giani, which were transported from the memorial chapel of the Monumental Cemetery of Milan and preserved on the wall of the museum in the first room, and Giani has the rare privilege of resting surrounded by the objects of the first proto-Celtic necropolis in the province of Varese which he himself discovered, publishing his analysis, in 1824. In the video, the director Massimo Palazzi talks to us about the characteristics of the Franciscan complex and takes us inside the rooms of the Museum.

The visit to the Museum begins in the cloister garden where there is a granite sarcophagus of Tito Primo Aproniano with an unrelated lid. with a double inscription, while in the portico there are three 17th-century statues from the Castle of Orago, and on the walls are tombstones adorned with the noble coats of arms of the Visconti, Lonati, Taverna and Rosso di San Secondo da Albizzate, the cover of the sepulchral crypt of Ugo da Laveno and the epigraph on the altar of Sant’Antonio granted by Pope Benedict XIV in 1752 from the demolished church of San Francesco.

Once inside, the findings from the archaeological section are arranged in chronological order over three rooms on the ground floor. The first of which is dedicated to prehistory and protohistory. While, the second and third to the Roman and early medieval ages. The exhibits on display come mainly from funerary contexts, typical grave goods from Roman necropolises which are the most extensively documented, with many of them coming from Gallarate attesting to the vitality of the area.

Necropolises funds

The necropolises allow us to understand more about funeral rite customs and the changes taking place over the ages. If, for the Celtic populations settled since the fourth century B.C., the rite dictated burial in the bare ground, with the Romanization of the territory starting from the second century. B.C., the rite of cremation spread, with changes also taking place in types of grave goods; for example the Gallic top-shaped cinerary vase was replaced by the Roman olla. The rite of cremation continued in the first centuries of the Empire until it was substituted by burial due to the spread of Christianity following the Edict of Constantine in 323, when it became the official state religion.

Urns were no longer used but instead tombs were used to house the body lying down. On the other side, the adding of various furnishings continued, a custom that would disappear in a later period. In the museum, there is an example of a burial from the Roman era called a “cappuccio” that was found in via Baraggia during random excavations in 1924, and which is a type of gneiss box with a quadrangular niche placed at a depth of 70cm, bordered by four large stone slabs 2.5m x 2. 3m and 1.6 in height with a thickness of 10cm, on a bare earth background and covered with gneiss.

Ceramics

Most of the material found is ceramic, used for pottery for domestic use with generally one specimen per type. Sometimes richly decorated with the use of a comb applied to the clay, but glass was also found in jars and glasses, and metal, iron and bronze in work objects such as knives, shears and arrowheads, a reflection of the economic and work activities of the time, as well as personal objects such as rings, bracelets, necklaces and mirrors. In some cases, coins were found, presumably to be used as offerings to pay the toll in the afterlife.

Finally, there were even fragments of animal bone and offerings of bread and dates. Of particular interest are the rare ceramic specimens that were covered with black paint based on mineral extracts and pine resin. This is in an attempt to imitate metal pottery, produced starting from the 4th century BC. in Campania, which provide evidence of trade with central Italy and the high social status of the deceased.

Underwater archeology

The Società degli Studi Patri carried out pioneering underwater archeology of the territory in the Neolithic Ligurian pile-dwelling stations in the lakes of Varese, Comabbio, Monate and Garda with findings consisting mainly of arrowheads in obsidian and quartz, fragments of pottery, vases, glass articles and copper artefacts including pins, tongs and daggers. Also, on display is a pirogue, a type of log canoe obtained by hollowing a tree trunk. Found in Lake Monate, the pirogue, due to its state of conservation, is actually one of the rare examples of a prehistoric boat that has come down to us.

Figurative art

Upstairs is the Gallery of Epigraphs, the Library with a historical archive. While, the art gallery featuring a collection of figurative art that covers a time frame from the Middle Ages to the 20th century. The collection, made up of paintings, sculptures, drawings and prints for a total of 112 items, was built up over time thanks to donations from Gallarate’s personal collections, and boasts pieces from famous artists. In 1986, the museum began the restoration of many of the preserved works.

Giuseppe De Alberti

Among the most noteworthy are the paintings with the family portraiture of Giuseppe De Alberti, an important neoclassical painter born in 1763 in Arona. De Alberti moved to Gallarate in 1840, and is notable for the photographic realism of his work and the meticulous detailing of the clothes. The painting The Painter’s Family was exhibited at the Gallerie d’Italia in Piazza Scala in Milan as part of the Romanticism exhibition in 2019, and at the Scuderie del Quirinale in Rome in the Ottocento Exhibition from Canova to the Quarto Stato in 2008.

Tanzio da Varallo

There are paintings donated by Virginia Caccia Marini in 1926, as well as the striking David and Goliath by Tanzio da Varallo. An artist born in 1582 in Valsesia, which is characterized by its ‘Michelangelo’s gigantism’ style. The action is captured at the moment of maximum muscular tension, and features a scenographic setting for the light source from the left and a black background, reminiscent of the style of Caravaggio who was known personally to the artists after meetings in Rome and Naples. This painting is a replica of the panel conserved in the Varallo Art Gallery. While, the altarpiece, Madonna Enthroned with Child, Saints and Musician Angels, is by Niccolò Pisano and dates back to the early 1500s.

Paolo Andreani

It was donated to the Museo degli Studi Patri by Rinaldo Martegani in 1963, from the Santini collection in Ferrara. Mantegani, born in Pisa in 1470, was Pietro Perugino’s assistant at the Sistine Chapel in Rome when he was very young. He spent most of his career in Bologna and Ferrara where he collaborated on the decorations of the Duomo. ‘Ascension of Paolo Andreani at Villa Moncucco’ painting by Francesco Battaglioli from 1784 depicts the second Italian flight, which took place in the park of Moncucco on 13 March 1784, a year after the first balloon flight by the Mongolfier brothers. The work constitutes an important element of the Museum’s collection for the minute details present in the painting of the park setting, the balloon and the spectators, but also in that it represents the Gallaratese’s vocation for flying.

In 1973, acknowledging the importance of the Museum, the then Superintendent of the Galleries of Milan Francesco Russoli temporarily entrusted to it five important paintings from the end of the 15th century. These paintings, owned by the Pinacoteca di Brera and previously exhibited at the Civic Museums of the Castle of Milan, are still in Gallarate.

Renzo Colombo

The exhibition itinerary concludes with a small but highly interesting section dedicated to sculpture. Including some artists who carried out works for the Monumental Cemetery of Gallarate. Of note are: the works of Renzo Colombo, an artist from Gallarate who lived during the second half of the 19th century. Whose works and some plaster casts were donated to the Società degli Studi Patri by his brother in 1896; fascinating sculptures by Adolf Wildt. The two Portraits of Alessandro and Carolina Trotti Maino donated by Carla Maino. And the Mater Purissima, which reproduces a detail of a larger work exhibited for the first time in Brera in 1918, donated by Monsignor Pietro Sommariva in 1932.

Adolfo Wildt

The artwork was included in the exhibition at Forlì at the Adolfo Wildt San Domenica Museums – The Soul and Forms between Michelangelo and Klimt. In 1921, the Milanese artist, who lived at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, founded the Marble School in Milan. Then it became part of the Brera Academy, and counted Lucio Fontana, Fausto Melotti and Luigi Broggini among his most famous pupils. Recognized as one of the best artists of the Liberty style with its symbolism, in these bas-relief works the artist manages to reconcile the purity and integrity of the forms with an intensely dramatic feeling.

MAGA Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art in via Egidio De Magri, 2009

The Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art called MA*GA has been in its current location since 2009. Its foundation actually took place in 1966, with the name of Civica Galleria d’Arte Moderna, in conjunction with the “Città of Gallarate” National Award for Visual Arts. It was promoted by a group of fellow citizens including the artist, and Professor Silvio Zanella became director until 1998, a position then filled by his daughter Emma, who is still in office, with the aim of supporting Italian art within an international context.

The architecture

In 2018, the museum, which is one of the most significant in the Lombardy Region, was recognized as a body of national importance by the Ministry itself. It stands on an architectural complex of over 5000 square meters that was designed by architects Maria Luisa Provasoli and Pier Michele Miano and created through the restoration of a former industrial structure with the addition of a new entrance characterized by a large, curved brick facade that seems to welcome the visitor in an embrace, a concept that recalls Bernini’s Piazza San Pietro. The layout of the bar inside the museum was instead designed by the Catalan artist Marti Guixé in collaboration with Ugo La Pietra.

The Museum counts the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and the Municipality of Gallarate as founding members, and the Region of Lombardy and the Province of Varese as institutional partners. Its aim is to promote contemporary art from the 20th century to the present day through exhibitions and initiatives such as temporary exhibitions, conferences, concerts, guided tours, art workshops and educational courses aimed in particular at children and schools. Since 2021 a new wing of the Museum has been become a study area and specialist library alongside the Majno Civic Library, effectively making up the new cultural center of Gallarate, HIC, Cultural Institutes Hub, and bringing to life the pioneering idea Professor Silvio Zanella had in the nineties.

A cultural center

The goal is to give life to a cultural center that works alongside a place of conservation and research. Also, the purpose is becoming a meeting point for young and old readers and the beating heart of a community spirit. Among the activities of the new HIC cultural center was the organization in 2022 of the first edition of ARCHIVIFUTURI, the Festival of Contemporary Archives.

A unique opportunity to uncover the cultural heritage of the 20th and 21st centuries in the area between upper Milan and the province of Varese. Also, up to the Swiss border, a territory characterized by the presence of museums, foundations, museum houses and archives that exceptionally open their offices to display the materials and works kept in them. The project was selected by the Lombardy Region within the scope of integrated, multi-sectorial cultural activities that require coordination between public and private entities.

International caliber

With the move to the new headquarters, the Museum is now of a national and international caliber. It became to all intents and purposes an important and active museum of contemporary art. Which, originating from its local context of active entrepreneurship above all in the textile sector, has, over time, enhanced the territory from an artistic and cultural point of view. The 100 works donated to the city by the Gallarate Prize in 1966 and exhibited in a small space of just as many square metres, are the heart of a heritage. This today has over 6,000 works by the best Italian artists including paintings, sculptures, drawings, installations, artists’ books, graphics, ceramics, photography and objects of design made starting form the Second World War, and covering various avant-garde, trans-avant-garde, post-modern, neo-futurism, multimedia art and radical design art movements.

Artistic heritage

The works come from the 26 editions of the Prize, basically from the numerous personal and free donations of Italian artists. They represent contemporary art which testify to the dynamism of an ever-growing collection. Among the most significant artists are Carlo Carrà, Mario Sironi, Renato Guttuso, Emilio Vedova, Bruno Munari, Fausto Melotti, Lucio Fontana, Dadamaino and Gianni Colombo. Just to name but a few. The growth of the collection has led to increased enhancement and support of the most current Italian art. Both produced by important artists as well as emerging artists. Through exhibitions and special projects, MA*GA is today an incubator of talents. A territory of well-rounded culture that never stops researching the great and most classic pictorial trends. Such as the recent exhibition on impressionism, or opening up to digital culture which, today, undoubtedly also affects the arts in all its forms. Photo www.museomaga.it

Return to Gallarate